Much like the sign I saw at the March this past weekend proclaiming “Too much to protest to fit on one sign,” I find myself nearly overwhelmed by the choices of all the terrible things that are happening to pick even one to blog about. So, in the time honored tradition of turning to Hollywood for relief, let’s talk about the Oscars.

Representation in Nominations

First, the good news. After last year’s #OscarsSoWhite, the Oscars did a bit better on the racial diversity front in their nominations this year:

While no actors of color were nominated the last two years, this year saw every acting category recognizing a person of color. A record-tying (with 2007) seven minority actors were recognized, including a record six black actors.

Moreover, people of color secured nominations for production, directing, writing, documentaries, cinematography, editing, etc. It seems crazy that the mere fact that someone other than white men received nominations is worthy of celebration, let alone mention. But here we are.

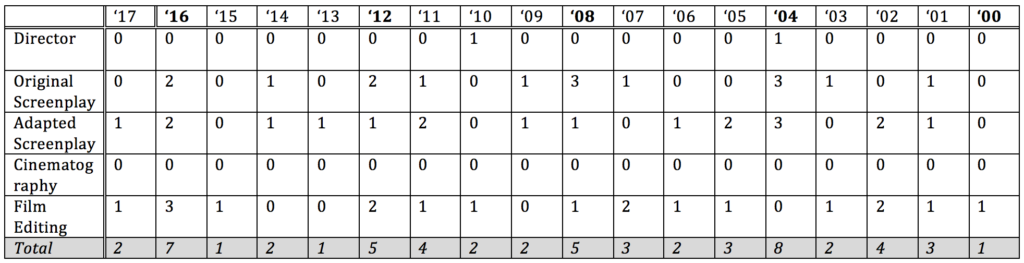

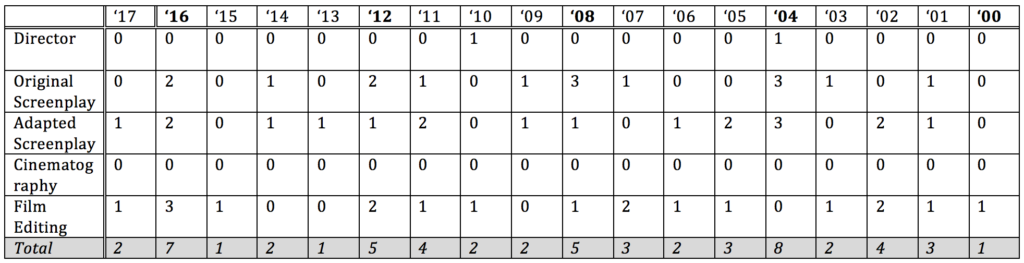

Which brings us to the less good news. The ladies. Or, in this case, the lack there of. Because, apparently, the white men of the Oscars can only nominate women OR people of color. Not both. Outside of acting, there are the big five categories for which individuals (rather than the movie writ large) receive awards — Directing, Original Screenplay, Adapted Screenplay, Cinematography, and Editing. In those categories, only two (2) women received nominations this year. Which seemed to me lower than the norm.

So I decided to go to the interwebs and map out nominations for women this century. Here is what I found:

Apparently, only two women nominated in the major non-acting categories is NOT out of the norm — for non-national election years. In 2016, 2012, 2008 and 2004, apparently there was enough discussion of identity politics that the Oscar voters checked their bias just a little bit more. That, or women only make worthwhile films in election years.

That the numbers for female nominees are shockingly low is not exactly news. I mean, the Oscar statue is literally a naked dude holding a really long sword in front of his groin. But also, the Women’s Media Center compiled a 10-year analysis (from 2005-2015) of the representation of women in Oscar nominations. Short story: the representation of women is pathetic and has been throughout time.

However far we’ve come, we have so much further to go.

Representation on Screen

But. I feel hope nonetheless. Because while representation in awards (and in the jobs available to women who then go on to win awards) is one very important piece, so is representation on film as well. Because what we see on film informs how we imagine our world and our place in it; who we see playing roles on film informs how younger generations understand the roles they can play in real life. And two films from this past year gave me particular reason to hope: Moonlight and Rogue One. Let’s take those in reverse order.

For those of you who somehow do not know, Rogue One, which received two Oscar nominations (for sound mixing and visual effects), is a part of the Star Wars series. It has, thus far, earned more than 1 billion dollars. It is a film whose star is, without qualification, a woman. There is no equivalent male star, and this made some men uncomfortable. It also has an incredibly diverse supporting cast. The most bad-ass of the supporting cast are two men who, depending on who you talk to, are either best friends who love one another or are actual lovers. And when I left the movie, I thought about what it means that children of this generation, who may very well grow up in a country much bleaker and more controlled by fear and hate than I would have hoped, will also have grown up seeing these men and women as undeniable heroes. Whatever social progress in government programs and priorities that this administration may roll back, it can’t make those powerful images unseen for the hundreds of thousands of people who have viewed this movie.

Moonlight, which received eight Oscar nominations (best picture, best director, best cinematography, best editing, best adapted screenplay, best supporting actor, best supporting actress, best score), is a small indie film that I see as most akin to a long-form poem on screen. So far, it has made less than 16 million dollars, but it has been shown in less than 700 screens. It is quiet and painful and beautiful. Each character — all of whom are black — is multifaceted and treated with a tenderness and compassion usually reserved for white characters. It presents pictures of masculinity that challenge the one-size-fits-all norm we usually see. When I left this movie (twice, so far — that’s how good it is), I couldn’t help but think of the students I’ve taught and what it would mean for them to see pictures of people they recognize, people who — however flawed — are still good. Who are shown loving and receiving love and who are shown as deserving of love. In times like these, images of love are just so damn necessary.